NOTICING LEAVES

aware of recent changes

and noticing leaves

I celebrate new growth

aware of recent changes

and noticing leaves

I celebrate new growth

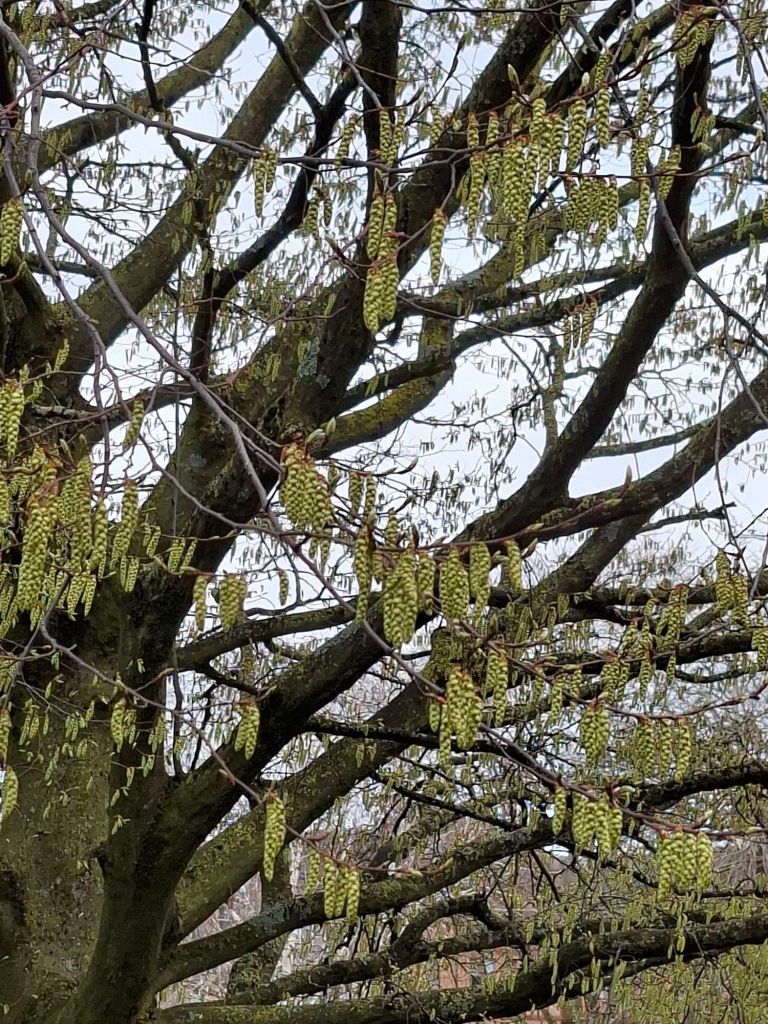

Within this changeable season, Wednesday 4 March was a notably bright day. Being present outside felt more vivid and state-altering than a similar experience on 25 February (1). Now, under a brighter, stronger sun I embodied the new season more confidently. For me, the pictures above and below record a new and subtly different moment in the year.

“Fence now meets fence in owners’ little bounds

Of field and meadow large as garden grounds

In little parcels little minds to please

With men and flocks imprisoned ill at ease …

Each little tyrant with his little sign

Shows where man claims, earth glows no more divine,

But paths to freedom and to childhood dear

A board sticks up to notice ‘no road here’ …

Thus, with the poor, sacred freedom bade goodbye

And much they feel it in the smothered sigh

And birds and trees and flowers without a name

All sighed when lawless law’s enclosure came.”

Poem by John Clare in Caroline Lucas Another England: How to Reclaim Our National Story (1)

Caroline Lucas comments: “in bearing witness to the impact of these changes, writers like Clare (2) formed the conscience of their time. One of the reasons that the enclosure movement was so powerful was that, seen purely in terms of short-term economics, it made sense. Having a whole field owned and farmed by one person was more ‘efficient’. And it was easier to control grazing if animals were confined to relatively small fields, rather than roaming about on large commons. Further, boosting the nations agricultural production could be seen as a ‘patriotic act’, good for England as well as for the landowner, and this helped those promoting enclosures to force them through in the face of popular resistance”.

Lucas goes on to cite the economic historian E. P. Thompson, who described Clare as a poet of ecological protest, whose radicalism lay in the fact that he ‘was not writing about man here and nature there, but lamenting a threatened equilibrium in which both were involved’.

The enclosure movement created landless labourers who had no choice but to take whatever work was offered by the new landowners, however low the wage. It was not planned or controlled for the good of the country, but in the interest of individual land holders and speculators. No provision was made for those who were displaced, even if they lost homes and livelihoods. Instead, enclosure was backed by the full power of the state, with anyone who objected liable to be tried, convicted and imprisoned or transported to the colonies – in this period (early C19th.) mostly Australia.

(1) Caroline Lucas Another England: How to Reclaim Our National Story Penguin Books, 2025 (First published by Hutchinson Heinemann 2024)

Caroline Lucas is a writer and campaigner. She was elected to Parliament for Brighton Pavilion in 2010, becoming the UK’s first Green Party MP. She also served as leader of the Green Party MP of England and Wales from 2008 to 2012 and as co- leader from 2016 to 2018 and, before that, was a Member of the European Parliament for ten years. She holds a PhD in English literature.

(2) John Clare (1793 – 1864) is described by his biographer Joathan Bate as “the greatest laboring-class poet that England has ever produced.” In the poem above he describes the natural, economic, cultural and personal trauma of the last and most intensive phase of the English enclosure process: a time in which most of the remaining traditional commons were forcibly replaced by private ownership.

Change is coming as the days lengthen and temperatures begin to rise. I too have begun to feel spring-like – more energised and available to the world.

Stepping out, I am in harmony with the life and growth around me. I become aware, again, of the resilience and potential of the plant kingdom.

I celebrate the life force within and without, both through movement as I walk and in stillness when I pause.

I learn again that a familiar space can be ordinary and extraordinary at the same time.

I open myself to spring 2026, the new season, as the Wheel continues to turn.

turbulent sky over quiet earth

dark clouds in motion

uncertainty in the now

4pm, 9 February, Gloucester Park. I notice the ground in front of my feet. New life is emerging, pushing through last year’s fallen leaves. Crocuses – yellow, white, mauve – are making themselves known. Recent rain gives the blades of new green grass a fresh vitality. Feeling curious and energised, I enjoy an extended moment of contemplation on this small patch of land.

Then, looking around me, I find a contrast between the ground – active, emergent, blooming – and the trees, with their skeletal branches and latent potential. The exceptions are the willows, already moving towards spring.

I reflect on my different states of attention. If I walk briskly through the park, the flowers in particular are easy to miss. They are small and not immediately arresting. To appreciate them, I have to decide to stop and look, emptying my mind of other concerns. Then I can become truly present to the world in front of me, a living world that wants to survive and thrive. Contemplating these flowers, I feel a strong sense of kinship and belonging. The same world is their home and mine: I feel grateful for being born into it. May the abundance of our world be protected and preserved in the days and years ahead.

Yesterday, 31 January, was a day for energy and enthusiasm. I stepped out briskly, mobilised to embrace this late winter afternoon with its spring characteristics.

In my morning practice (see https://contemplativeinquiry.blog/2026/01/28/) I identify a season of ‘winter, dying and regeneration’. Yesterday I both embodied the regeneration I had liturgically named, and saw regeneration all around me. This experience confirmed that, for me, Imbolc is a late winter festival that announces something new. It anticipates spring, whilst not quite being part of it.

I find great comfort in following the wheel of the year. My eager anticipation of spring is simply a moment in the year, which happens every year. I do not have to wait for spring as if for emancipation or redemption in linear time, anxious about whether I will live to see it. I can simply enjoy this moment, which happens to be anticipatory, at this time.

I was walking in the later afternoon. The picture above was taken a little before 4pm and the picture below a little afterwards. I noticed that after many weeks, I was not feeling a primal prompt to hurry back to shelter at this time and thereby avoid the dark. We now have nine hours of sunlight in the day, rather than the eight of the Solstice period. Most of the extra hour has been added to the afternoon. I became fully aware of the experiential difference during this walk.

The pictures themselves were not central to this walk. But they are relevant to its contemplative theme. I was delighted to see two swans together by the canal bank. Because the image is of a pair, I was reminded of their mating time from March onwards – no longer so very far away. I am always heartened by the sight of swans thriving on this stretch of water.

The picture below is of strong late afternoon sunlight striking a dredger in the Gloucester docks, where the canal begins. For me, it is a strong image of the returning light in late winter. I also saw the sun as empowering and blessing a machine that digs down and cleans up, working energetically in unseen depths to help maintain a larger system.

I want to say something about my regular morning practice as it has developed in recent months.

Compared to earlier iterations, I have stripped my practice down and abbreviated it. Although solo, it relies on speaking and at times moving (eg to greet directions). It has become more affirmative than meditative or prayerful, though elements of prayer and meditation are included. It is grounded in an animist and panentheist Druidry, finding a depth dimension in the here and now of this world. It doesn’t reference any named or personified deity.

I have used material from my past work in Druidry, and to a lesser extent Buddhism and the Eckhart Tolle community. But I have stylised and adapted these influences better to sound my unique note in the Great Song.

To begin, I light a candle, sound my Tibetan bells three times and say: I arise today in the strength of heaven, light of sun, radiance of moon, splendour of fire, speed of lightning, swiftness of wind, depth of sea, stability of earth and firmness of rock.

May there be peace in the 7 directions:

May there be peace in the east, power of light, element of air, domain of the hawk, quality of vision, time of sunrise, season of spring and early growth.

May there be peace in the south, power of life, element of fire, domain of the dragon, quality of purpose, time of midday, season of summer and of ripening.

May there be peace in the west, power of love, element of water, domain of the salmon, quality of wisdom, time of sunset, season of autumn and bearing fruit.

May there be peace in the north, power of liberation, element of earth, domain of the bear, quality of faith, time of midnight, season of winter, dying and regeneration.

May there be peace below, in the deep earth and underworld.

May there be peace above, in the starry heavens.

I abide in the peace of the centre, the bubbling source from which I spring, and heart of living presence. May there be peace throughout the world. May I be present in this space.

I begin a breath exercise: breathing in through my nose, counting to 8; holding, counting to 8; releasing, counting to 8, resting, counting to 8. I repeat this 11 times. Then I say: I am the movements of the breath and stillness in the breath; living presence in a field of living presence in a more than human world: here, now, home.

I say: A blessing on my life. May I be free from harm; may I be healthy; may I be happy; may I live with ease. A blessing on my life.

A blessing on Elaine’s* life. May she be free from harm; may she be healthy; may she be happy; may she live with ease. A blessing on her life.

A blessing on the lives of our kin. May they be free from harm; may they be healthy; may they be happy; may they live with ease. A blessing on their lives.

A blessing on the lives of our companions. May they be free from harm, may they be healthy, may they be happy, may they live with ease.

A blessing on all lives we touch and are touched by. May they be free from harm; may they be healthy; may they be happy; may they live with ease. A blessing on their lives.

A blessing on all beings throughout the Cosmos; may we be free from harm; may we be healthy; may we be happy; may we live with ease. A blessing on our lives.

A blessing on our lives (arms raised), a blessing on the work (hands over heart), a blessing on the land (hands on ground).

I say: In the heart of Being I find protection,

and in protection strength;

and in strength, understanding;

and in understanding, knowledge;

and in knowledge, the knowledge of justice;

and in the knowledge of justice the love of it;

and in the love of justice the love of all existences;

and in the love of all existences, the love of this radiant Cosmos. Awen (Aah-ooo-wen, as a chant).

May there be peace throughout the world. May I be present in my life.

I stand today in the strength of heaven, light of sun, radiance of moon, splendour of fire, speed of lightning, swiftness of wind, depth of sea, stability of earth and firmness of rock. I ring my bells three times and extinguish my candle.

*NOTE ON PICTURE: original photo by me and stylised by my wife Elaine Knight with AI support.

The year has moved on from its midwinter moment. I am just beginning to feel the pull of Imbolc (Candlemas in the Christian year). This feast marks the returning light and early signs of spring. I recently saw a local picture showing a newborn lamb.

In the Gaelic traditions Imbolc/Candlemas (1 February) is dedicated to Brigid/Bride. The lines below are from the Scottish Highlands and Islands. They seek protection and are not specifially seasonal.

“The genealogy of the holy maiden Bride

Radiant flame of gold, noble foster- mother of Christ.

Bride the daughter of Dugall the brown,

Son of Aodh, son of Art, son of Conn,

Son of Crearar, son of Cis, son of Carmac, son of Carruin.

Every day and every night

That I say the genealogy of Bride,

I shall not be killed, I shall not be harried,

I shall not be put in a cell, I shall not be wounded,

Neither shall Christ leave me in forgetfulness.

No fire, nor sun, nor moon shall burn me,

No lake, no water nor sea shall drown me,

No arrow of fay nor dart of fairy shall wound me,

And I under the protection of my Holy Mary,

And my gentle foster-mother is my beloved Bride.”

Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations collected by Alexander Carmichael. 1994 edition by Floris Books, Edinburgh, edited by C. J Moore.

The work is an anthology of poems and prayers from the Gaelic oral tradition in Scotland. They come from all over the Scottish Highlands and Islands. Alexander Carmichael compiled the collection in the second half of the nineteenth century, thereby creating a lasting record of a culture and way of life which has now largely disappeared.

music that celebrates Earth and speaks to the heart

Follow the Moon's Cycle

Meeting nature on nature's terms

A little bit of Mark Rosher in South Gloucestershire, England

A monastic polytheist's and animist’s journal

Selkie Writing…

Images and words set against a backdrop of outsider art.

living with metacrisis and collapse

The pagan path. The Old Ways In New Times

Spiritual journeys in tending the living earth, permaculture, and nature-inspired arts

a magickal dialogue between nature and culture

The gentle art of living with less

Thoughts about living, loving and worshiping as an autistic Hearth Druid and Heathen. One woman's journey.

An place to read and share stories about the celtic seasonal festivals

Just another WordPress.com site

Exploring our connection to the wider world

Become more grounded and spacious with yourself and others, through your own body’s wisdom

Good lives on our one planet

News for the residents of Hopeless, Maine