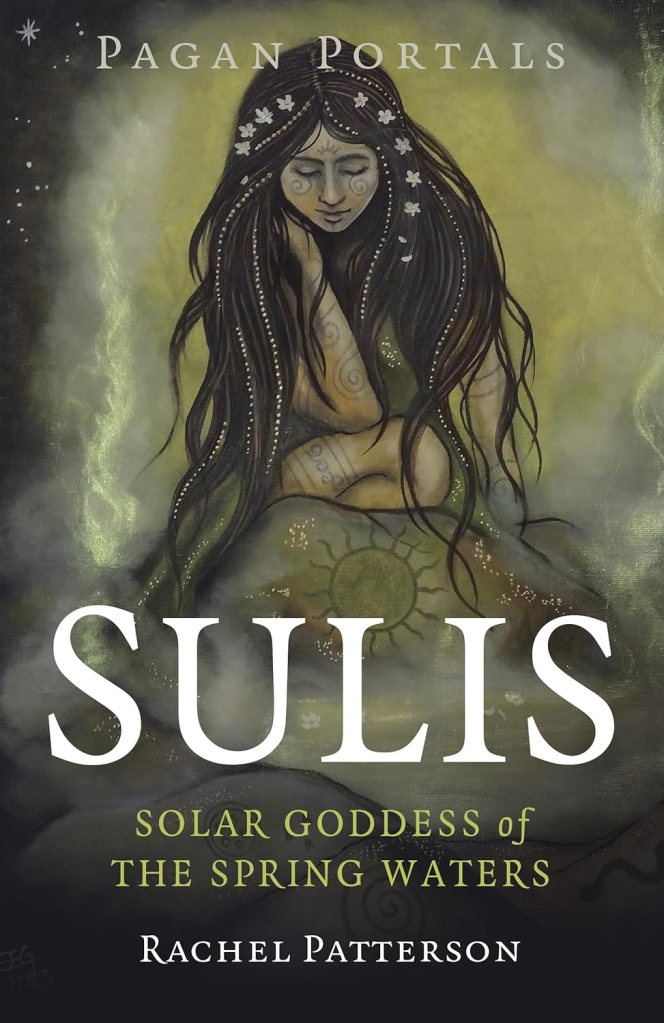

BOOK REVIEW: SULIS, SOLAR GODDESS OF THE SPRING WATERS

Recommended especially to two overlapping groups: first, readers interested in Sulis (later Sulis-Minerva) the presiding deity of the hot springs at Bath, UK; second, readers interested in polytheist Paganism in Britain, both ancient and modern. Author Rachel Patterson describes her heart as that of an English Kitchen Witch and her craft “a combination of old religion witchcraft, Wicca, hedge witchery and folk Magic”. Hence in this book she focuses not only on the history of Sulis and her springs but also on how to work with Sulis today.

The hot springs at Bath are the only ones in the country, appearing after the last Ice Age around 12,000 years ago. The people who re-settled the land as hunter gatherers began leaving offerings at the springs around 9,500 years ago. They continued to do so for several thousand years until the appearance of farming. We have no record of their beliefs, but for them the numinous power may well have been the living presence of the springs themselves, rather than a presiding deity.

The farmers, when they came, seem to have left the springs alone. But early in the first century CE a causeway of gravel and mud was placed in the main spring pool. Offerings were made, principally of coins minted by the local Celtic tribe, the Dobunni. Pottery was also found but there were no buildings. In 43 CE the Romans invaded Britain and quickly established themselves in the south. The Dobunni chose peace and an accommodation with the Romans, who soon created a spa, building on top of the natural springs. They adopted the local goddess Sulis, now to be known as Sulis Minerva. A town gradually grew up, named Aquae Sulis (The Waters of Sulis). A temple and sanctuary began to be built in 70 CE. The baths are now well-kept after an up-and-down history, and are open to visitors. See http://www.romanbaths.co.uk.

Rachel Patterson describes how the temple worked in the Roman period. Many of the extant records are written curses from people whose clothes and possessions were stolen while they bathed. They asked the Sulis for retributive action in return for offerings and the lost possessions themselves (1). Patterson also describes the decoration of the temple and artifacts from it. The best known was once called the gorgon’s head but is clearly the head of a male figure. He seems to be associated with a god named Belenus, who may in turn be connected with the legendary King Bladud included in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the King’s of Britain (2,3).

The second half of Rachel Patterson’s book is about working with Sulis. It is a thorough and practical guide for readers who may want to go down that path. It includes sections on making candles and altars dedicated to Sulis; on finding Sulis; building a relationship with her; advice on oath-taking; and the development of rituals and meditations dedicated to her. There is relevant advice on the use of herbs, crystals, forms of divination, petitions and curses. There are sections on animal companions and (pigs and wild boar as the Celtic contribution, owls and dolphins related to Minerva). As a Kitchen Witch, Rachel Patterson also provides a number of recipes.

I have lived both the first and most recent 20 years of my life within a forty mile radius of Bath. I don’t go there very often. But I have known it from an early age and bathed in the waters during the more recent period. There is indeed something magical about them. So I’m glad to see Sulis taken more seriously. There is a familiar problem about limited information from the past and Rachel Patterson discusses this in her book But for me there is enough resonance from the old times, here, to dream the myth onwards. I can’t assess the practical guidance offered in Sulis: Solar Goddess of the Spring Waters because I don’t work in the same way. But I do know it is comprehensive and comes from a seasoned practitioner. It feels to me like a timely addition to the Pagan Portals series, and I am grateful to have it.

(1) Further information about religion in Roman Britain, and its rather transactional nature, can be found in Prof- Ronald Hutton’s Gresham College lecture on Paganism in Roman Britain. See https://contemplativeinquiry.blog/22/12/12/paganism-in-roman-britain/ – where a link to the lecture is provided,

(2) see picture and narrative at https://contemplativeinquiry.blog/2021/03/23/the-sacred-head-of-bladud/

(3) For creative treatments of the story of Bladud and the Goddess Sulis, see Kevan Manwaring’s account in The Bardic Handbook and two novels by Moyra Caldecott: The Winged Man and The Waters of Sul